In 1903, when aviation was still in its infancy, a 19-year-old woman successfully flew an airship on her own. Her achievement, however, was carefully hidden by her family and never reported in the press, out of fear of society’s negative reaction. They worried that no man would want to marry a woman who had done such a daring thing. But that fear could not hold back her courage, curiosity, and determination. Though Aida de Acosta’s successful flight was kept secret for a time, in 1932 she herself revealed the story, along with photos of the flight, ensuring her place in aviation history.

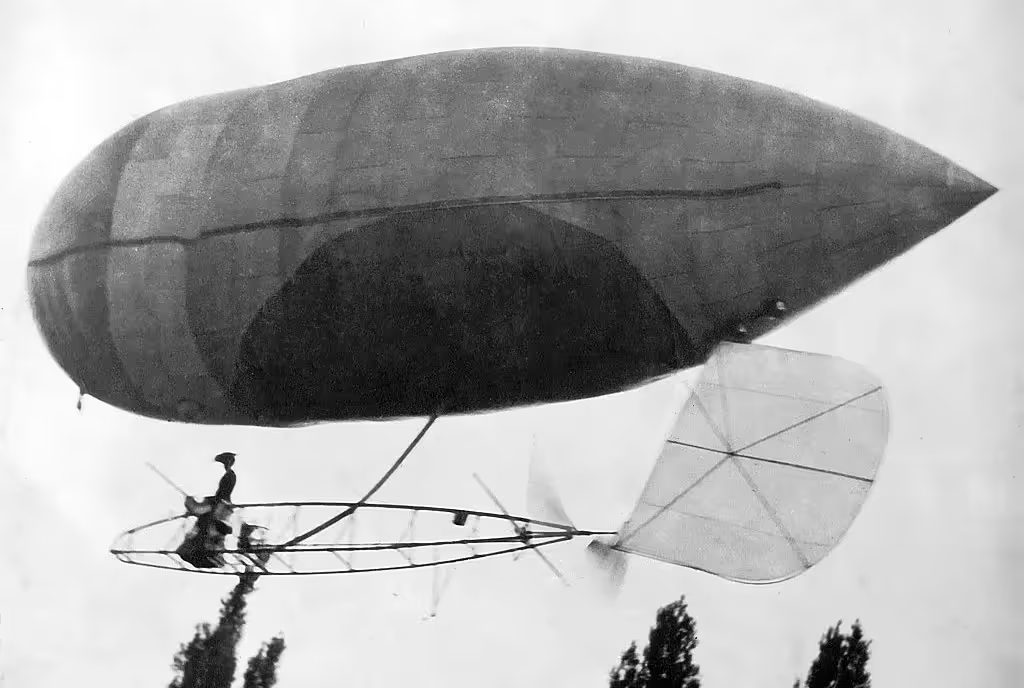

In Paris in 1903, Aida de Acosta, fascinated by aviation, witnessed Alberto Santos-Dumont flying one of his self-designed airships. She asked to learn, and Santos-Dumont personally taught her how to operate a single-seat airship.

Alberto Santos-Dumont, the Brazilian aviation pioneer, became famous in 1901 when he won a prize by flying his airship around the Eiffel Tower and back within a set time. He was also known for flying to his favorite Paris restaurant in his airship and “parking” it on the street while dining. In 1906, his flight with the 14-bis became one of the first documented cases of a powered airplane taking off, flying, and landing under its own power. For this reason, many Europeans regarded him as the true inventor of flight. Santos-Dumont believed flying machines should be accessible to everyone, not just a select few. His decision to teach Aida de Acosta, and even entrust her with his personal airship, No. 9, was proof of this belief.

After just three lessons, Aida de Acosta flew Dumont’s Baladeuse airship solo, from Paris to Versailles, becoming the first woman to fly a powered aircraft alone. Her historic flight took place during a polo match between American and English teams, where spectators cheered her on. The journey lasted about an hour and a half. After landing, a famous exchange was recorded:

Aida de Acosta: “It was beautiful, Monsieur Santos-Dumont.”

Santos-Dumont: “Mademoiselle, you are the first woman aeronaut in the world!”

Despite the press wanting to cover the story, Acosta’s family pleaded with Santos-Dumont to keep it quiet, fearing scandal if word spread that the daughter of a prominent New York family had done such a thing. Santos-Dumont agreed. In his 1904 book My Airships, he described her, calling her beautiful, kind, passionate, and determined, but never revealed her name.

Although family pressure forced her to give up flying, Acosta later became a pioneer in another field. In 1922, she lost sight in one eye due to glaucoma. She dedicated the rest of her life to advocating for eye health, raising major funds for research and treatment. In 1945, she became the director of America’s first eye bank in New York. She never reconnected with Santos-Dumont and passed away in 1962.

Santos-Dumont’s ideas and inventions greatly shaped aviation. Since he needed both hands to control his aircraft, it was impractical to check the time with a pocket watch. He shared this problem with his friend Louis Cartier, the French jeweler and watchmaker. In 1904, Cartier designed a wristwatch for Santos-Dumont—one of the first men’s wristwatches ever, created specifically for a pilot. Today, the Cartier Santos and Santos-Dumont watches carry on that legacy.

While Santos-Dumont dreamed of aviation as a tool for human progress, he was deeply troubled when airplanes were used for war. Haunted by this misuse, he suffered greatly and tragically took his own life in Brazil in 1932. Though he never married, it is said that a photograph of Aida de Acosta always stood on his desk, beside a vase of fresh flowers.