In 1986, the Wall Street Journal used the term Glass Ceiling for the first time in a report on “Women in the Workplace.” The glass ceiling describes the invisible and insurmountable barriers that stand between women and upper management, preventing their advancement regardless of their achievements and merit. Although this term was not coined in the 1950s, the gender norms of the era and the male-dominated structure of the aviation industry led to Adile Tuğrul and her team being dismissed from their duties as flight attendants.

Adile Tuğrul, who had a childhood passion for flying, was appointed as a staff member at Devlet Hava Yolları (State Airlines) in 1948 and later began working as a flight attendant, a profession she described years later as “something that should exist in Turkey.” Devlet Hava Yolları is the flag carrier airline of Türkiye, known today as Türk Hava Yolları (Turkish Airlines). The airline’s assignment of female flight attendants on flights, passengers’ growing familiarity with female attendants, and Adile Tuğrul’s in-flight successes all contributed positively to passenger satisfaction and enhanced the company’s prestige. For these reasons, the dismissal of Adile Tuğrul and other female attendants can be explained through the lens of the glass ceiling syndrome.

While Adile Tuğrul was successfully performing her duties in 1948, female flight attendants were first removed from their posts in 1950, with Tuğrul herself losing her position as a flight attendant soon after. Between 1950 and 1953, Turkish Airlines did not assign female flight attendants on flights. Although this was often framed as a socio-cultural issue, the influence of institutional factors should not be overlooked. Considering that the State Airlines Enterprise was founded in 1933 and renamed Türk Hava Yolları Anonim Ortaklığı in 1956, the airline was striving in the 1950s to align with international civil aviation standards, enhance its corporate image, and provide more professional service to foreign passengers. It was therefore illogical for the airline to discontinue the use of female flight attendants at that time. Moreover, while female flight attendants were common in European and American airlines, it is not reasonable to claim that Türkiye’s social structure was unsuitable for women to perform this role.

The airline was a public institution at the time, and there are criticisms that political and bureaucratic influences played a role in this decision. This situation, which restricted and even blocked women’s professional advancement, was later described by Adile Tuğrul herself with grace as “a period when it was necessary to take a break.”

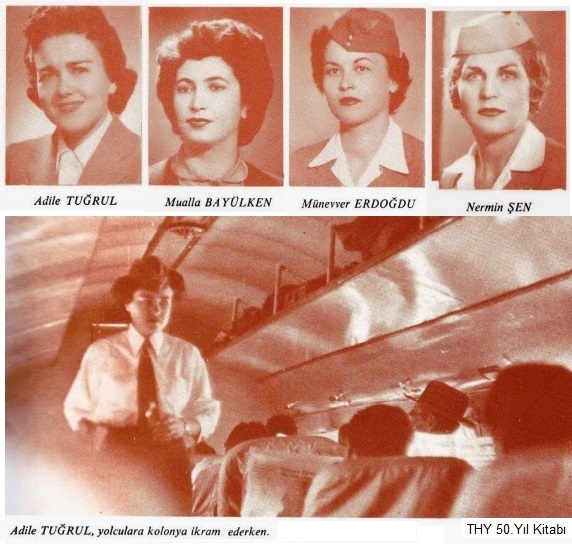

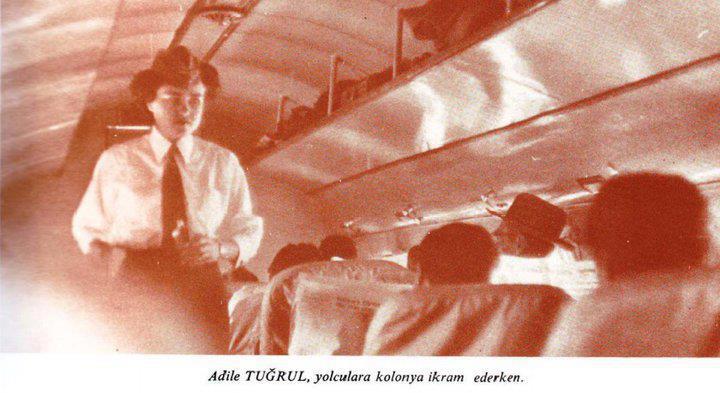

Between 1953 and 1960, Adile Tuğrul enthusiastically and successfully continued her career as a flight attendant at Türk Hava Yolları and emphasized the importance of the profession for Türkiye. Proving the success of women in aviation, Tuğrul became a significant figure in Turkish aviation history. Years later, Turkey’s national aviation authority, the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (SHGM), awarded her the title of “Türkiye’s First Female Flight Attendant and Cabin Crew Member” through its Gender Balance Development initiative. Her contributions were instrumental in laying the foundations of today’s cabin crew profession.